NEW LAUNCH: Weill Cornell Medicine's Maya app is now available for Android!

NEW LAUNCH: Weill Cornell Medicine's Maya app is now available for Android!

This sometimes overlooked skill is critical to the successful and timely delivery of software. How does thoughtful and strategic ticket writing help our team at Heady stay on top of fast-moving projects? This blog explores the essential skill of how to write agile tickets and best practices that every product manager should know.

Product management involves not just strategic planning but also delivering on those strategies, which accounts for a substantial portion of the job — about 90%, in fact. Clear direction and coordination are vital for effectively delivering on a strategy.

A Heady Product Manager must master the foundational skills of effective ticket writing in order to achieve all the other tasks and goals that are central to success in their role, including:

It's time to debunk the misconception that ticket writing is merely filling out a template. Here we'll dive into the nuances that separate a mediocre ticket from a rock star ticket. By learning and embracing these guidelines, you’ll build your strengths as a product manager — and once you’ve mastered the rules, you’ll be able to strategically break them as needed.

The first step in mastering ticket writing is understanding what makes an effective ticket or user story. At Heady, we use agile INVEST principles.

In an ideal world, agile tickets should be:

Now let's see how these principles translate into a new signup feature for our imaginary product.

The best way to cover the INVEST principles is actually to shuffle them around a bit. Let's start with V=Value.

To begin, let’s look at the basic user story outline:

As a <user>

I want to <function/unit of work>

So that <value>

This structure enables us to articulate the user value (V from our INVEST principles). However, the task involves more than just filling out this user value template.

Differentiating between the intended user action and the actual user desire is crucial. It may seem straightforward, but this is where many product managers stumble.

A simple example is:

As a user, I want to sign up so that I can log in.

While the difference may seem minor, its significance becomes apparent when prioritizing stories with multiple stakeholders. By being specific and clear about feature value, we can guide stakeholders more effectively and prioritize faster, making our work more efficient overall.

But let's take it further.

It's easy to default to a generic “user,” but most products have various target audiences and personas. A user story becomes stronger if it emphasizes a specific type of user instead of a generic one. Again, while it may not seem like a big difference, these tweaks can help save time and hone in on the most valuable stories and features.

So let's drill down further and add more specificity to our story:

As a repeat shopper, I want to sign up so that I can make my purchase more quickly.

Now we've established that we're creating value for repeat shoppers, the kind of user for whom a business definitely wants to provide an exceptional shopping experience.

Product managers are asked to add business value by adding product value. If we're able to add value with every single prioritized user story, then product value becomes inherent in our process and business ROI will always be positive. Our clients will be happy, our users will be happy, and the product will grow.

When identifying the user in a user story, it's important to:

When identifying the value of a unit of work in a user story, it's important to:

Next on our INVEST principles roadmap is S=Small.

The definition of 'small' may vary across organizations, so let's clarify what it means at Heady. We view 'small' as something achievable within a two-week sprint. Tasks expected to take longer than two weeks will likely have unknowns and be segmented into additional steps. While this isn’t a rigid rule, it serves as a handy guideline to keep tickets manageable without overwhelming the team.

We can also test 'small' with Acceptance Criteria (more detail on this later!) and should ideally keep the ticket’s Acceptance Criteria below 8. We can break this rule in some cases, but 8 is a good, quick litmus test.

Let’s return to our example from the previous Value section and build on it:

As a repeat shopper, I want to sign up for an account so I can make my purchase more quickly.

We've all experienced many different signup flows, and they vary — so it's hard to say definitively whether this user story is small. As with most things in life, it depends!

Extra Credit: As a product manager, you should have some basic understanding of how data flows. More often than not it's via APIs. But if you're just startng out, look at a design and think about the user action at each stage. Discuss assumptions with your engineering team until you get more comfortable with the lingo.

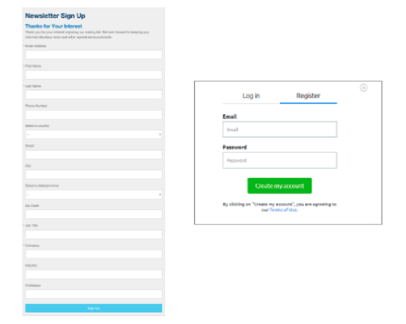

Now, let’s look at two different signup screens:

Even someone with minimal tech knowledge can easily see one screen requires many more inputs than the other.

The right screen is probably small enough to be one user story. The left screen, on the other hand, probably needs to be broken up into multiple user stories to keep the tasks small and manageable. Examples of additional user stories we may create for the left signup screen are:

As a shopper, I want to add my address so I can check out faster.

As a shopper, I want to add my credit card information so I can check out faster.

As a shopper, I want to provide my preferences so I can get relevant product recommendations.

Keeping user stories small is helpful to product development in many ways. Small user stories make it easier to track your team's work, avoid additional back and forth because of multiple unknowns, and address delays (if any) more quickly.

A few important notes to keep in mind:

Next in INVEST is I = Independent and N=Negotiable.

Keeping tickets small makes them more manageable. Manageable tickets are also independent, meaning they can be worked and shipped independently of any other ticket.

Why is this important? If tickets are small in scope but they have multiple dependencies, then they’ll suffer from the same downsides as big tickets: blocked engineers, increased back-and-forth, and decreased visibility into what's completed and can be shipped.

Ensuring all tickets are both small and independent may seem ambitious or even unrealistic. But when engineers are challenged to break out the work into small, independent tasks, they tend to find implementation solutions that work for everyone. Once everyone on the team is aware that all tickets need to be independent, a joint effort can help flag if there are dependencies and the team can work to uncouple where possible.

Here we're grouping I=Independent and N=Negotiable together because both rely on getting sign-off and feedback from your engineers.

Because they allow for input from team members with different perspectives, tickets that are negotiable tend to lead to better outcomes. That said, there are some best practices to follow in collaborating with engineers.

It's important to remember that engineering can be both subjective and creative. There can be multiple ways to approach a problem and some engineers default to either how they've done it in the past or challenging themselves with something completely new. In both cases, it can be valuable to facilitate a ”pros and cons” conversation about different implementations.

For example, implementing signups with one framework may lead to a speedier delivery, but the maintenance of that code may be more time-consuming in the long term.

Encouraging engineers to get a second opinion will help surface tradeoffs that may not be clear from the outset. But keep in mind that a product manager should be pragmatic with his or her time. Trying to spark a conversation for every single ticket is not feasible for most, so you'll want to focus extra attention on features that use new technology, are time-sensitive, or are high-priority for the client.

Product managers should be fluent enough in tech to spark relevant conversations with their engineers so they can maintain independent and negotiable ticket structures.

So far in our journey through the INVEST roadmap we've explored business goals, defined a valuable user story, and laid out best practices for getting input from engineers. Now we’ll tackle how to determine whether a ticket is feasible. This is where we put rubber to the road with the definition of 'done'.

Now let's move on to the next INVEST principles on our list, E=Estimable and T=Testable.

A ticket is only estimable if you've provided enough information and included Acceptance Criteria.

Acceptance Criteria help us define what 'done' is. It's a way for the product manager to clearly state what they expect to see on the user side once a ticket is complete.

If Acceptance Criteria aren't met, the user story has not passed and should be kicked back to development.

If Acceptance Criteria are met and the end result is not as expected, the user story should be kicked back to business analysis.

A ticket can have multiple Acceptance Criteria. Each will have three parts:

The Given, or precondition, is the condition the app is in before the action takes place. When creating the acceptance criteria, here are some important things to keep in mind:

The When specifies the exact user action the product manager will be testing. Example: Adding an item to the cart is a user action.

The Result is what the product manager is expecting to happen when the user action takes place.

Including this information in a ticket provides engineers with enough detail to estimate the unit of work, while also addressing how it will be tested.

That leads us to our final INVEST principle, T=Testable.

To explore what a testable ticket looks like, we’ll return to our example user journey:

As a shopper, I want to add an address during the signup process so I can make my next purchase more quickly.

Here we've defined what the user wants to accomplish. The acceptance criteria below are examples of steps in the user journey that can be tested, making it clear to the entire team the definition of 'done' for this ticket.

Acceptance Criteria # 1

Acceptance Criteria # 2

Acceptance Criteria # 3

Acceptance Criteria # 4

And that’s how to complete a ticket using INVEST principles!

Effective ticket writing is a cornerstone of agile product management. It enables a team to break down complex projects into manageable, valuable pieces of work that can be independently developed, easily estimated, and thoroughly tested.

By following the INVEST principles and putting effort into crafting clear and comprehensive user stories, you can help your team deliver high-quality software consistently and efficiently.

Remember, a well-written ticket is more than just a task: It's a conversation starter that encourages collaboration and leads to superior outcomes. Practice makes perfect, so if you are looking for additional challenges, here’s something you can try: Screenshot your favorite app and start to break out that feature into a user story with acceptance criteria.

It may seem daunting in the beginning, but as you grow in your product management role, you should always be striving to refine your ticket-writing skills. Your team, your clients, and your users will thank you for it.

Our emails are (almost) as cool as our digital products.

Your phone will break before our apps do.

© 2026, Heady LLC.